2017 Jazz Gallery Residency Commissions: Adam O'Farrill Speaks

This weekend, The Jazz Gallery is proud to kick off our 2017 Residency Commission series. For this year, the Gallery has commissioned work from three young musicians who have already been making waves in the New York jazz scene—vibraphonist Joel Ross, saxophonist Maria Grand, and this weekend's performer, trumpeter Adam O'Farrill.Since being a finalist in the 2014 Monk Competition, O'Farrill has made the leap from budding talent to force-to-be-reckoned-with. He has made head-turning appearances on recent records by Rudresh Mahanthappa and Stephan Crump and released an acclaimed debut album with his group Stranger Days on Sunnyside just under a year ago (which you can check out below).For his Residency Commission, O'Farrill has composed an evening-length song cycle dealing with the feelings of loss and paranoia through the lens of contemporary environmental issues. Titled "I'd Like My Life Back," the song cycle finds O'Farrill synthesizing a huge range of influences, from the art rock of Nick Cave to the vocal music of Benjamin Britten. We caught up with Adam by phone to discuss his motivations for the project and how he managed to give such a sprawling composition a unified through-line.The Jazz Gallery: Where did the title of your project come from?

This weekend, The Jazz Gallery is proud to kick off our 2017 Residency Commission series. For this year, the Gallery has commissioned work from three young musicians who have already been making waves in the New York jazz scene—vibraphonist Joel Ross, saxophonist Maria Grand, and this weekend's performer, trumpeter Adam O'Farrill.Since being a finalist in the 2014 Monk Competition, O'Farrill has made the leap from budding talent to force-to-be-reckoned-with. He has made head-turning appearances on recent records by Rudresh Mahanthappa and Stephan Crump and released an acclaimed debut album with his group Stranger Days on Sunnyside just under a year ago (which you can check out below).For his Residency Commission, O'Farrill has composed an evening-length song cycle dealing with the feelings of loss and paranoia through the lens of contemporary environmental issues. Titled "I'd Like My Life Back," the song cycle finds O'Farrill synthesizing a huge range of influences, from the art rock of Nick Cave to the vocal music of Benjamin Britten. We caught up with Adam by phone to discuss his motivations for the project and how he managed to give such a sprawling composition a unified through-line.The Jazz Gallery: Where did the title of your project come from?

Adam O'Farrill: The literal origin of the title comes from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. The CEO of BP Oil's response to all the damage was this: "We're sorry for the massive destruction it's caused their lives. There's no one who wants this over more than I do. I would like my life back."This quote in particular is a pretty dark example greed and corporate interests minimizing the struggle of people who've actually been impacted by environmental issues. The CEO is trying to paint himself as the real sufferer.I've been thinking a lot about issues like this since the election. I feel that among the people I know, there's been a big awakening since then, people becoming more socially aware, a greater sense of responsibility. But there's also this aspect that during the Obama era, we took care of ourselves a little less because it felt like we had someone in power who cared about our interests more. Now, we're really having to fight more for what believe in, so in the process, we're putting out personal needs aside a little bit in service of the bigger picture. So it's also a bit of wanting my own personal enjoyment back with all this stuff going on that we have to deal with.With this message in mind, I wanted to capture the feeling of dread that's been in place for the past several months. It's very much a post-Obama piece.

TJG: One of the difficulties of writing music with socio-political messaging is that the message can overpower the music, making the whole experience feel preachy. How have you dealt with these potential pitfalls and have there been any particular political music inspirations you've drawn from?

AO: Right away, knowing my own tastes, I knew I didn't want my music to be preachy, or explicit in its message. There are some great artists whose music can be really explicit in this regard, like what Samora Pinderhughes has done with his Transformations Suite, where the message is explicit in this really great way. And my dad has done work with Cornell West. But I was going for something more focused on that feeling of dread, more than the issues themselves.I found that environmental issues were, figuratively speaking, fertile ground, musically. There are so many great representations of nature and the environment throughout music history. One of the pieces in this project is called "Six Degrees of Removal" and it's about the six-step process of mountaintop removal coal mining, which has been happening all throughout Appalachia. Each step is a different action. For the step of clearing, I wrote this arpeggios that move all over different registers. And then for the step of blasting, I had these sporadic and bombastic instrumental hits. The last part is called reclamation, which describes the after-effects of the mining. They call the blown out mountains moonscapes because of the way they look, really barren and indented. I represented that with funereal, dirge-like music. There's voice over all of that and the voice fits with the music by focusing on more poetic lyrics, rather than just describing what happens.

TJG: It sounds like you're exploring different means of musical storytelling to communicate metaphorically about the environmental issues, rather than explicitly.

AO: Exactly. I think because the subject is more technical than say the Civil Rights Movement, you have to approach it differently.

TJG: In addition to Samora Pinderhughes and your dad, were there other artists whose work you explored as you were working on the project?

AO: I'd say the two principle artists that I thought about with this project were Benjamin Britten and Nick Cave, for very different reasons. The way this project began was that Nathan Campbell came out to a show of mine this past winter. There's something really operatic and really theatrical about the way he sings and it definitely reminds me of Nick Cave. At the gig, we talked about Nick Cave and our mutual admiration for him, and then kind of half-seriously I told him about the commission. He was getting ready to go off to Turkey to teach English, but also because he's always been fascinated by Turkish culture. So he was getting ready to move, but I told him that if it could work out logistically, would he be interested in doing some kind of Nick Cave like thing on the project. He was into it and then committed a few days later.My interest in Nick Cave also coincided with a growing appreciation of the Japanese author Yukio Mishima. They both have this really special way of dealing with bleak subject matter. They talk about death and desire and they do it in a way that inspires feelings of both sadness and amazement at the same time. That's something I really wanted to capture with this music—something that was bleak, but also had this radiance.Another thing I've loved about Cave is how his band plays. They really mix a lot of free and experimental elements within conventional forms. And like you said about storytelling earlier, Cave definitely has an interesting way of telling stories with his music. A lot of his songs are filled with these beautiful descriptions.With Benjamin Britten, I took this class at the Manhattan School of Music on him and his work that was probably the best class I've ever taken. It was a semester-long class and I listened to a lot of music. He dealt with a lot of serious subject matter in his music, but he was able to find this fantasy in it. As bleak as the subjects he wrote about were, the music always had this shining quality to me. There was also always an interesting balance between very melodious writing and more murky writing—harmonically, timbrally, formally. It wasn't murky in that it was all shrouded in darkness, but more like you don't know what specific gestures are supposed to mean, but they just are. I really loved that. The way Britten wrote for voice was also really big for me, and Nathan is a huge fan of Britten as well. It's a good pairing.

TJG: Completely! The thing I'm always struck with in Britten's work is that he can deal with dark subjects in very different ways musically. He can do it on a large scale in his operas or the War Requiem, and then he can do it in these really heartbreaking and intimate ways in pieces like his Holy Sonnets of John Donne. It's not just dark, but different exquisite shades of darkness.

AO: Yeah! Just so many shades.One of my favorite pieces is his Serenade for Tenor, Horn, and Strings. There's one movement in particular that I love called "Pastoral." The music was in part inspired by the landscape paintings of John Constable. There was a big volcanic eruption in Indonesia in 1815, which had a huge impact on weather all over the world. The aftermath had a big influence on painters like Constable and J.M.W. Turner and inspired them to paint the sky in different colors, like with lots of orange. My teacher helped me see a lot of those ideas reflected in Britten's serenade. A lot of the harmonies in the piece would sound pleasant if they were voiced in root position and in a clear register, but Britten refits and recolors them to give them a more ominous sound, even in major keys.

TJG: It's as if different parameters in a piece of music have different emotional connotations. Like major or minor keys connote certain emotions, as do different tempos, or different registers. Many times, those parameters complement each other, but Britten is taking parameters with contrasting connotations and melding them together to make a more complicated emotional landscape.

AO: Right. That's what I love about Britten. I feel he led an interesting life. He lived in a time of a lot of experimentation in the classical music world, but he always stuck to his guns. Truthfully, there's a lot of stuff that I admire with experimentation, but it's not always what I want to do. With Britten, he didn't really let that get in the way of expressing himself. That may be why he doesn't get talked about the same way as some of his contemporaries.

TJG: One thing you mentioned about both Britten and Nick Cave is how they did interesting, surprising things within conventional forms. How did this thinking affect how you planned the overall structure of your piece?

AO: At the beginning, Nathan and I produced a loose structure, a map of things we wanted to touch on. I then began a musical sketch of each section to get their vibe and figure out the whole arc. I definitely took little melodic ideas and figured out how to reapply them in different sections. My main thought process behind that idea was thinking about the themes as ensemble characters in a film. I really love the movies of Paul Thomas Anderson and I'm definitely inspired by Magnolia for certain. It's cool because it's a three-hour move that takes place over the span of like two real-life hours. You see these characters come back and interact in these crazy ways, and I was really inspired by that in terms of making motifs and melodies interlock in my piece.I was also influenced a lot by Johnny Cash and traditional Mexican music when laying out the different sections of the piece. In Mexican music, there will be like seven or eight bars of singing and then several bars of an instrumental interlude, like with the guitars. It's similar in a lot of Johnny Cash's music—these uneven trades between the voice and the rest of the band.There's something really satisfying about composing that you don't really get when you're playing. There's this long term process going on when you're composing. When you're improvising, you're trying to make things work in the moment, especially in terms of building on ideas. But when you're composing, you can have these moments where you bring something back where the listener may not expect it, or two parts line up in this really satisfying way.

TJG: You have a pretty sizable group coming to the Gallery for this piece and it has a pretty varied instrumentation. What went into putting together the group? Did you want particular instruments or particular players?

AO: A little bit of both. They're all great musicians and great people, and all people who I've played with before in some capacity, though in widely different contexts. What's exciting to me is that a lot of the players don't really know each other. The first person I asked was Jasper Dutz, before I had any idea of what the project would be. I had seen his senior recital and I was blown away. Russell, Daryl, and Travis—I've played with them the most out of everyone, so that was an easy call. With Russell in particular, I really liked that he has a strong rock background, but he's also studied with Billy Hart. I played with Patricia Brennan in a few different situations and I had never used vibes before. I wanted to have that different color, and a different challenge. Larry Bustamante plays in my dad's band. I had Jasper first, and then I thought of Larry because I specifically I wanted to play with two bass clarinets and both of them play great bass clarinet. I thought that would be a really interesting sound to work with.

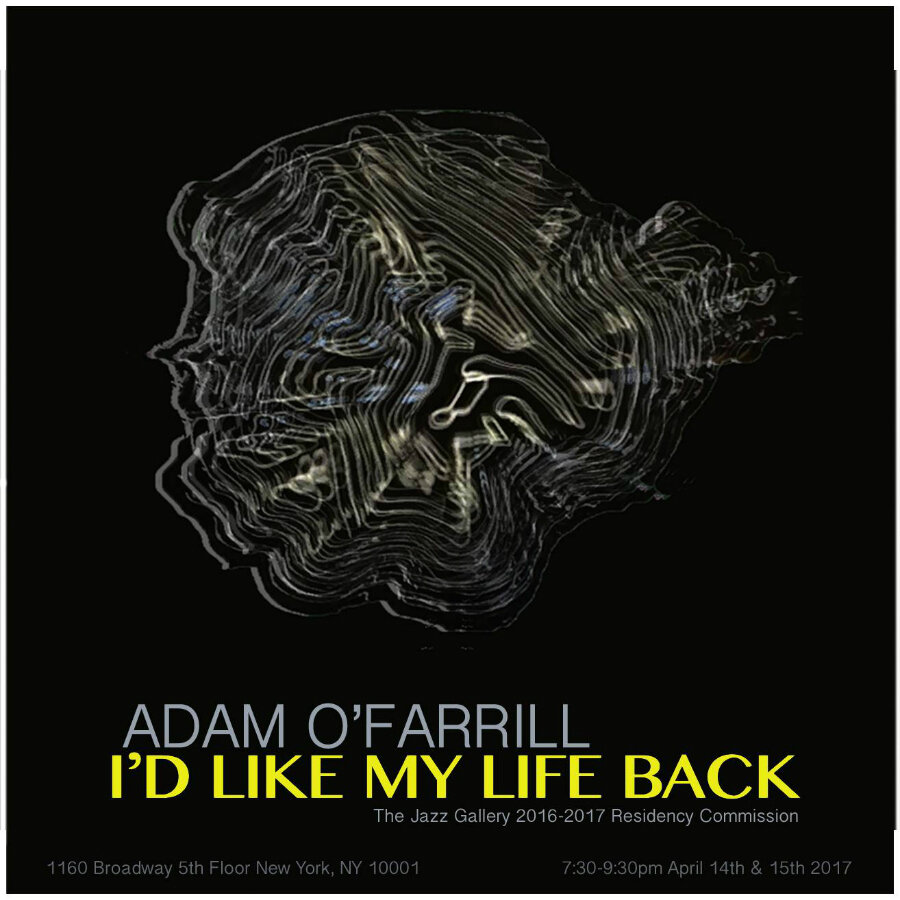

Adam O'Farrill performs his 2017 Jazz Gallery Residency Commission I'd Like My Life Back at The Jazz Gallery on Friday, April 14th, and Saturday, April 15th, 2017. The group features Mr. O'Farrill on trumpet, Patricia Brennan on vibraphone, Larry Bustamante and Jasper Dutz on woodwinds, Travis Reuter on guitar, Daryl Johns on bass, Russell Holzman on drums, and Nathan Campbell on voice & lyrics. Sets are at 7:30 and 9:30 P.M. each night. $22 general admission (FREE for members) for each set. Purchase tickets here.