Creative Disruptions: Miles Okazaki Speaks

Miles Okazaki has brought his swaggering, high-concept quartet to the Jazz Gallery many times over the past decade. But don’t expect a retread at his Tuesday and Wednesday sets: his quartet has brand new personnel and material. After spending much of 2015 with Steve Coleman’s Five Elements band, Okazaki has grabbed its rhythm section, Anthony Tidd on bass and Sean Rickman on drums, for himself. They’ll be joined by preeminent pianist Craig Taborn and debut “Trickster,” which is slated to be Okazaki’s fourth album. (The group will record next week and plans to release the album this year.) In an interview, Okazaki spoke on the idea of the trickster, his evolving relationship with guitar, and writing a book; excerpts are below.The Jazz Gallery: Can you tell me about the idea of the Trickster and how you became interested in the idea?

Miles Okazaki has brought his swaggering, high-concept quartet to the Jazz Gallery many times over the past decade. But don’t expect a retread at his Tuesday and Wednesday sets: his quartet has brand new personnel and material. After spending much of 2015 with Steve Coleman’s Five Elements band, Okazaki has grabbed its rhythm section, Anthony Tidd on bass and Sean Rickman on drums, for himself. They’ll be joined by preeminent pianist Craig Taborn and debut “Trickster,” which is slated to be Okazaki’s fourth album. (The group will record next week and plans to release the album this year.) In an interview, Okazaki spoke on the idea of the trickster, his evolving relationship with guitar, and writing a book; excerpts are below.The Jazz Gallery: Can you tell me about the idea of the Trickster and how you became interested in the idea?

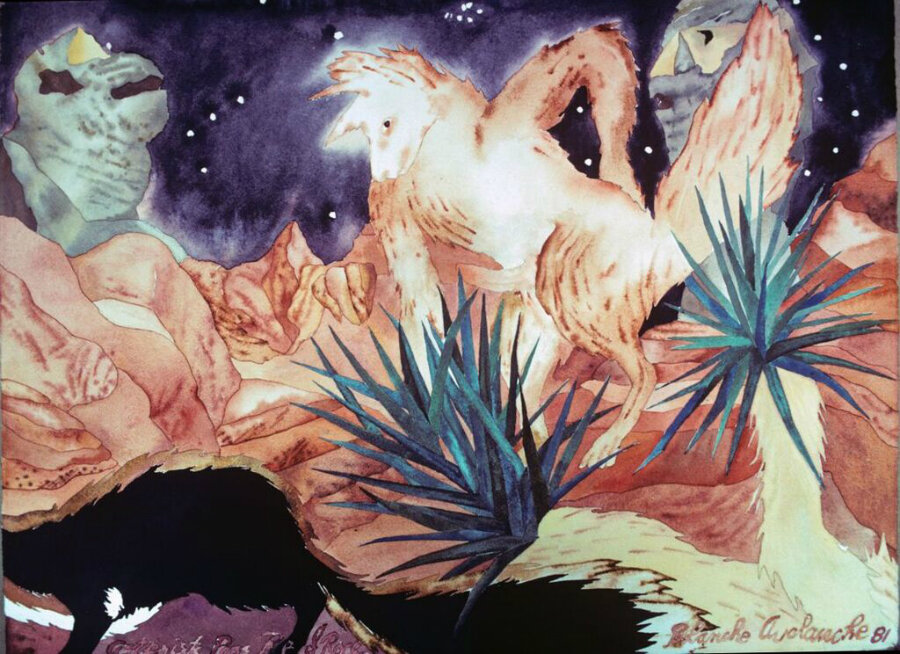

Miles Okazaki: In the back of my mind I was always interested in it because my mother is a painter, and it’s a theme in her paintings. She always had these ravens and coyotes.

A couple years ago, I was reading “The Book of Imaginary Beings,” by Borges. One of its characters is called a heyoka. This is a character who does everything backwards: up is down, he rides a horse backwards, etc. He has these sticks that he uses to beat out rhythms and make a thunder. I thought, “this guy is like an improviser!” It just sparked my interest.My mom sent me this book called “Trickster Makes This World” by Lewis Hyde. That opened up a bunch of stuff. I started looking at all these different characters and stories, and they all just seemed really musical. You have an area where something is comfortable and things are in order, and an area where things are chaotic, and there’s this borderline area. That’s where these trickster figures operate. They operate by bringing people across that border, or by transgressing the border themselves and making it okay for people to do it. Or showing people what’s possible on one side or another of the border, or by disrupting the order so that new things can be created.The creative function of these figures is, I feel like, musicians from the past. Somebody like Thelonious Monk, this very mysterious person... That idea of the origin of how do we get to the next thing: that’s what I’m looking for. I’ve done a certain amount of stuff, I need to break it up and get to the next thing.

TJG: So how did these ideas manifest in the music?

MO: There’s a famous one about the raven. He finds a hole in the sky, he goes to the other world, and the light is inside of this infinite nest of boxes. He steals the light and that becomes the sun. That has a lot of musical things in it. First of all, it has this thing about two areas. So in this song there are these two harmonic areas, and they’re bridged by this little melody. Rhythmically, there’s a thing happening that’s like nested boxes.

TJG: How do the trickster and the musician relate?

MO: Improvising musicians are like these trickster figures in that we exist in between stuff. People still like to go out and see live music: there’s something happening there ritualistically. It’s a form of storytelling, people communicating with sound in real time, that is gone after it’s done and never to be repeated again. That’s something special. That points to musicians as bearers of this tradition of live storytelling.And opening up doorways, possibilities, for ourselves, for others. That’s the way we progress, by discovering new things, in a live situation, where things are slightly out of control. You get to those places where things open up and you can go a little bit farther. If people are there, they see it’s possible. Once people see something as possible, it becomes part of the common knowledge.

TJG: What did you take from playing with Steve Coleman this year?

MO: It’s essential for certain bands to do a lot of playing to really get their own sound. Steve’s philosophy is to take that to the extreme, where he really wants the band to be operating on a reflex type of level. His stuff is not based on charts and setlists: it’s more based on a whole sort of language that he’s developed. The learning curve, for me, is pretty steep. But I’m getting there. (laughs)

TJG: How long did it take to feel comfortable within the group? Or is comfort not the point?

MO: Comfort is definitely not the point. It’s about maybe something more like the opposite, trying to push it all the time. To the point where it’s in control but slightly on the edge of not being in control. That’s that liminal area where things happen. I think he does a really interesting job in leading the group into that place consistently.

TJG: You’re bringing Coleman’s rhythm section, Sean Rickman and Anthony Tidd, into your own group. What’s special about their connection?

MO: I first went to see them with Dan Weiss to see them at the Knitting Factory in 1999. It freaked us out. We didn’t have any idea what was going on. Sean’s playing freaked Dan out, which I had never seen before. He’s pretty impervious to getting freaked out.They have some very special stuff that’s really impossible to quantify or write down. Let’s say you give an improvising musician a set of chord changes to improvise over. They’re not gonna just play the chords: they’ll play some melodies that are based on that thing, that is underlying but not being explicitly stated. Those guys can do that with rhythm. Instead of repeating a same rhythm, that rhythm can be in the background like a melody that you’re referring to, and with these variations on top of it.

TJG: Usually your quartets are with a saxophonist. How will you interact with another harmonic instrument—Craig Taborn on piano—in this project?

MO: I think of the guitar less as a harmonic instrument than a rhythmic instrument. That’s one of the reasons I wanted the piano: to deal with the harmonic information, because there’s a lot of it.My previous records didn’t focus on my own playing. I wasn’t really interested in taking big solos. I don’t really care about that. But I spent a few years writing a book on the guitar and doing some more research into the instrument, and as a result, I got more into my instrument, how it works, and how I play personally. I felt like featuring that a little bit more. So people who are not used to seeing me play a lot will see me play a lot.

TJG: Is this project a break from the compositional cycle of your last three albums?

MO: No, nothing is a break. I’m still writing the same music I was writing ten years ago. It’s just I’m finding ways to get across the ideas with more economy, and with more purpose.My idea for this project is that all the music physically feels good to play. You’re not forcing yourself into these twisted up knots to try to make the notes. I did it deliberately in order to get some stuff that’s gonna jump into groove territory pretty quickly and not be too egg-headed. Balance out the physical and mental a little better.

TJG: You published "Fundamentals of Guitar" last year. What was the process of writing a book like?

MO: I thought I was gonna lose my mind when I was writing that book. I didn’t realize what a big deal it was. That solitary thing is really rough.It’s quite detailed and obsessive. In a way it’s good because I got that off my back now, I don’t need to look around for practice material. I can only actually do a small percentage of things that are in that book. Everything is one idea and then all the possible things you could do with that idea based on what I could imagine.

Miles Okazaki's Trickster plays The Jazz Gallery on Tuesday, January 12th, and Wednesday, January 13th, 2016. The group features Mr. Okazaki on guitar, Craig Taborn on piano, Anthony Tidd on bass, and Sean Rickman on drums. Sets are at 7:30 and 9:30 P.M. each night. $15 general admission ($10 for members) for each set. Purchase tickets here.