Eleven Cages: Dan Tepfer Speaks

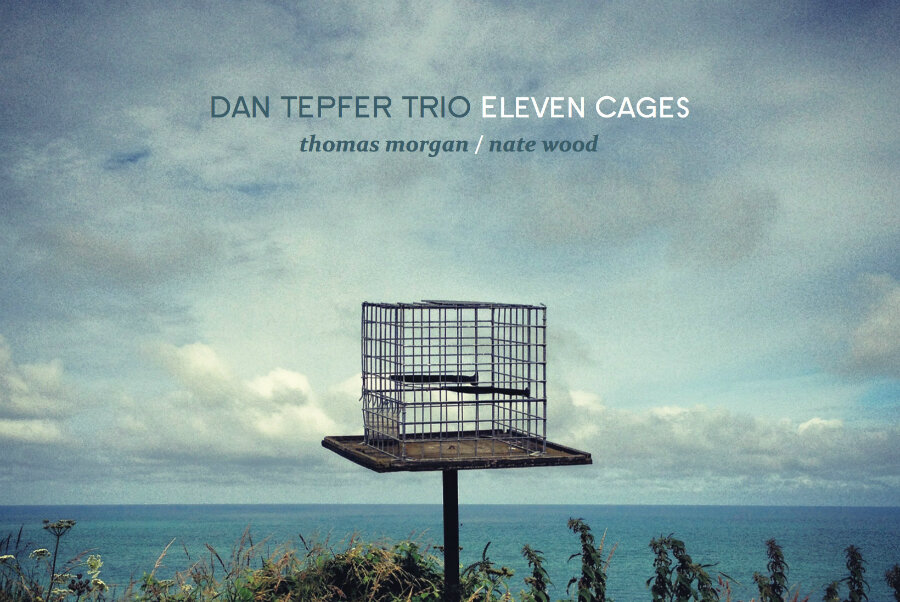

Dan Tepfer, a Jazz Gallery regular, will release his new record Eleven Cages (Sunnyside) this week. The immersive album features drummer Nate Wood and bassist Thomas Morgan, working through the challenging and probing compositions of Tepfer, as well as several unexpected covers. As always, Tepfer’s playing is remarkable, exhibiting grace, dexterity, and a sharp, mindful approach to improvisation. Along with Morgan and Wood, the three approach Tepfer’s music with levity, enthusiasm, and hyper focus.

For this two-night release, the Dan Tepfer trio will include Wood on drums, as well as bassist Or Bareket. We spoke with Tepfer about the recording process, the details on developing his left hand technique, and some of his compositional concepts.

TJG: Diving right into the sound on the album—the drums have so much air, and the piano and bass meld together so well. The ‘live’ trio sound really pulls the listener in: Walk me through the preparation and recording process.

Dan Tepfer: I’ve made all my recent records at the Yamaha performance space in New York, starting with my Goldberg Variations/Variations record that came out in 2011. I’ve been a Yamaha Artist for the last seven years or so, and am lucky to have a relationship with them. For the most part, I’ve recorded these records myself in their space. For this session, Nate and I co-engineered it, using our own gear. It was literally just the three of us in the studio, which I love. If the music needs more space or time, it’s not going to cost more money. You’re not on the clock. I took a lot of time with the mixing process: I had a residency last summer at the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire, where I was composing a piece for string quartet and piano. While working on that piece, I did my own mix of the album. I mixed it all again in New York with Rick Kwan, then Nate mastered it—he’s an amazing engineer.

TJG: A live record is a performance, in many ways. When we talked last about your work with Lee Konitz, you spoke about preparing for the moment, being ready to let go and be free on stage. Knowing that you’d be doing one-room recordings, did it inform your composition and rehearsal process?

DT: There’s a limited amount of editing you can do, sure. I wouldn’t say the recording method dictated the composition process: These are tunes I’ve written over the last five or six years. Putting this record out feels very cathartic for me. It’s a lot of music I’ve been wanting to get out there for a long time. Above all, each tune is an idea, a system of constraints that we work our way through. But there are actually a couple of free tracks on the record that have a lot to do with the space we’re in. Those are some of my favorite tracks on the record, because there’s nothing preplanned about them. We’re just listening hard and playing together in the space.

TJG: I’m glad you brought up the concept of the cage, of constraints. The album has eleven tracks; eleven cages, eleven different confines to explore?

DT: That’s kind of the idea, that cages make you more free. In the United States, we have ‘the tyranny of choice’ in many ways. I’ve gotten so much out of restricting my choices and seeing what can happen in that environment.

TJG: How have you personally found positivity in understanding and growing within your limitations?

DT: Well, I wouldn’t call them “my limitations,” per se; they’re limitations I choose to impose on myself. I see it as a positive thing: I think we’ve all experienced this, especially people who’ve grown up on the boundary of the internet age. The internet is just constant stimulation. So, one thing the internet never gives you is the opportunity to be bored. I grew up without a TV, and as an only child, being creative was something I did to entertain myself. When you restrict your options, it allows you to get bored, and subsequently fight your way toward something new. It’s all about keeping yourself psyched. The problem with having too many options is that you don’t have to work very hard to keep yourself psyched.

TJG: I think I hear you; I’m just missing the connection between being bored and constructing limitations for yourself.

DT: Look at a piece by Ligeti called Musica Ricercata. Each movement, he only allows himself a certain number of notes. In movement one, he only uses one note. It’s part of the score for Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, actually. Ligeti uses the note in octaves, in different rhythms, but only the one note. There are plenty of movements in Musica Ricercata, with different amounts of notes, but that first movement has something special. Can you imagine how hard you have to work to make things cool if you only have one note? He has a lot of fun with drama, tempo, dynamics, rhythm. Basically, the constraint brings it to life. The constraint makes you bored, then challenges you. That’s where the real creativity lies. You have to rely on your ingenuity, not old tricks that you’ve relied on before. If you’re never in that tough spot, you can never really have that experience of catharsis. So, constraints allow you the possibility for catharsis.

TJG: For pianists, one of the biggest constraints is often the left hand. On “Roadrunner,” it took me two listens to realize that your left hand was playing in unison with the bass through your solo, until about 3:00. And on “Single Ladies,” the left hand also has a pretty hefty role, rarely playing block chords and really animating the low end. Tell me a bit about the development of your left hand sound.

DT: I grew up playing a lot of Bach from the conservatory in Paris. Bach was really the center of my musical education. I’ve always loved the music. In general, I love symmetry. I’ve been playing and performing the Goldberg Variations a lot over the last six years. At some point, I realized that one of the most amazing things about Bach is that his keyboard music is incredibly symmetrical for the performer. A lot of problems are caused by asymmetry in the ways we use our bodies. Violinists have it kind of tough; saxophonists often have one shoulder that’s higher than the other. With Bach on the keyboard, if you’re doing it right, you’re playing in a very symmetrical way. As I got deeper into the Goldberg and began performing them, I thought, ‘You know, it’s crazy that when I play jazz, I’m not anywhere as symmetrical in the use of my body as I am when I’m playing Bach.’ I’ve always been a left hand advocate, but I started working hard on being able to hear my left hand in just as melodic a capacity as my right hand around that time. It feels important to me on a basic level.

TJG: It absolutely comes through on the album. Ligeti makes some wild demands of the left hand as well.

DT: Totally. That particular etude that I play quite often, the “Fanfares” etude no. 4, has a great left hand part. Ligeti was a brilliant guy who taught harmony and counterpoint. He wasn’t just a modernist—he knew the history of the music like few other people. That etude is a great example of the symmetry I’m talking about. It feels like a bassline, but actually that line keeps getting passed between the left and right hands. The crazy counter-lines he creates happens just as much in the left hand as it does in the right. That study is a perfect example of what I’m talking about.

TJG: Parts of "Minor Fall" reminded me of "Chelsea Bridge" from Keith Jarrett’s Whisper Not, especially when Nate gets more active with the mallets. You cite Jarrett as an influence on I Loves You Porgy as well: Is he a big influence?

DT: Definitely. I think the way I think about music is pretty far from where he’s coming from at this point, but I listened to him a lot growing up. He’s definitely a big influence. I admire him for the breadth of the music he makes, his total commitment to doing everything at the highest level, taking care of time and voice leading, melody, harmonic motion. Always unbelievable. Total emotional commitment too, and unbelievably prolific.

TJG: He’s got the trio too, of course. What other piano trios do you look towards, in terms of their negotiating the cage?

DT: I almost hesitate to put the Keith trio in that list. That trio is great, but they only play standards. There’s one record where they play free, but basically it’s standard repertoire. [My new] record is really a composer record above all. But you know, I’ve always loved the piano trio. I grew up listening to it a lot. I listened a lot to Ahmad Jamal, Monk, Brad Mehldau in my teens, Jason Moran trio, Vijay Iyer. Basically, I like people who are executing the music at a high level but also have ideas. That’s really important to me.

TJG: I’m just realizing, as you’re naming all these piano trios, you’re naming all these pianists as the frontmen. I wonder, is there a canon of bass trios or drum trios?

DT: That’s a good question. One that comes to mind is that record with Jack Dejohnette, Music We Are, with Danilo Perez and John Patitucci. That’s a powerful group, and it’s totally lead by Jack. Of course, he also plays melodica on it, and he’s a great pianist. I’m sure there are a number of other examples of piano trios lead by drummers and bassists. I’ve done piano trio gigs as a sideman. I did a gig with George Schuller and Jeremy Stratton, and that was George’s recording. That was a piano trio. A few months ago, I did a gig with Alexis Cuadrado. Piano trio but his gig. It’s all about who writes the material, who pays the band, you know? [Laughs].

TJG: You mentioned that Cage Free I and Cage Free II are free improvisations, right? What was the context for putting them on the record? Did they come at the end, did you do them first, do they play a narrative role in the progression of the record?

DT: The narrative of the record, for me, comes at the end. Maybe some day I’ll write a whole record with that in mind, but with this, I had a lot more material than made it to the record. There are a solid five or six tunes that are not on there, of which we recorded good versions. The question for me was getting a good progression of tunes on the album. Jerome Sabbagh helped me with that. It’s so helpful to have someone to bounce ideas off in terms of sequencing. The free tunes had a lot to do with the space. We’re in the space, trying to play together, and playing free improvisation is a great way to try to find that. That’s something I’ve done a lot with Lee Konitz as well. So I had the tunes, I listened to them all, those two especially. As I was working a sequence out, they felt like good palate cleansers between the heavier tunes. It’s hard to say what order this stuff comes together in, it’s like arranging pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

TJG: Thomas seems to take more of a leading role on the free pieces—was that a conscious decision?

DT: It wasn’t conscious, per se. When I’m playing free, I think a lot about this Paul Bley quote, which I’m about to misquote, but basically, that you should never step into a musical situation unless it really needs you. So you should only play if something needs your help. I think about that a lot. If the music sounds good on its own, I want to stay out of it, not play, you know? I’ve found that Thomas and Nate were creating such beautiful stuff together that I was just enjoying sitting there listening.

TJG: I love the triads on "Hindi Hex;" reminded me a little of "What The Waves Brought," by Tigran Hamasyan. You describe the rhythmic motion of "Hindi Hex" in the liner notes, but tell me more about that harmony.

DT: I’ll tell you the secret behind the tune: I had a duo series a few years ago at an art gallery in the east village. I had Miguel Zernon, Billy Hart, Rebekah Heller, and Gilad Hekselman. There was a concert a week, and for each person, I tried to write a bunch of new material, often trying to use their names in some way. For Gilad, I wrote Hindi Hex. If you say the letter “a” is C, “b” is C#, “c” is D, and go through the alphabet like that, I figured out what notes “HEKSELMAN” spells out - it’s almost a diminished scale, with one note that’s out, and I though that it was a cool 9-note motif. It made me think of these North Indian patterns that drummer Richie Barshay taught me many years ago. And so, the notes correspond to Gilad’s name, and correspond to the rhythms of this specific North Indian rhythm. Underneath it, major and minor triads are moving through the diminished scale, so you get this really interesting motion. It’s funny, sometimes something you haven’t thought about in years seems like the perfect thing.

Speaking of narrative, that’s a tune we recorded with the trio. But when I was putting the record together, I felt like it wanted something. There’s a duo piece, and there’s a bunch of trio pieces, and I felt like it needed a solo piece right in the middle of the record. That piece is there, right in the middle. It’s a structural, narrative decision, with regard to how the tunes are paced. So I recorded it with the trio, and then did another solo version.

TJG: So you have the trio version tucked away somewhere?

DT: I do. Great Thomas Morgan solo on it actually. I mean, that’s almost an oxymoron, because every Thomas Morgan solo is great, but it was kind of heartbreaking not to put in on the record, because it was really amazing.

TJG: I’ll be looking out for the B Sides.

DT: Exactly, the Japanese edition [laughs].

TJG: The continuous chromatic motion of Little Princess reminded me of a Shepard Tone, where you hear a steady-moving pitch and can’t remember where it began or where you’re going. How did that tune come together?

DT: It’s funny you bring that up. I’m a fan of that kind of stuff. A few years ago, when I was first starting to use SuperCollider, I programmed some Shepard Tones. There’s something compelling about chromatic motion. It’s so obvious, seems like such a basic building block, but you can do a lot of things with it.

TJG: It’s sort of a “Minute to learn, lifetime to master” thing, where the chromatic scale is so simple, but you use it in a complex and compelling way. As soon as the track starts, you know it’s going to be a chromatic thing, but you can’t guess how it’s going to unfold.

DT: That’s one of my favorite tracks on the record. It feels like something pretty different, bringing together the things I like. It’s a bit nerdy too.

TJG: So at the Gallery it’ll be you, Nate, and Or Bareket, yes?

DT: Exactly. Thomas, who plays on the album, is an incredibly unique musician. I write some music with some challenges to it, and he seems to understand it immediately. Or Bareket is also a beautiful musician. He’s younger, incredibly committed to getting it right. One of the most positive attitudes, and a really deep rhythmic feel. I’ve never played with him and Nate, but I have a positive feeling about it. I think it’ll work out well.

TJG: Any more thoughts about releasing the CD at The Jazz Gallery?

DT: Absolutely. I so deeply value what the organization has done, Rio in particular. I think it’s so important. I played at The Gallery for the first time in 2007 with Lee Konitz. Since then, I’ve played there with a number of other people, and my trio, more times than I can count. This will be just a little more than ten years since the first time I played there, so I’m excited to be coming back to experience the new space and the new piano.

The Dan Tepfer Trio celebrates the release of Eleven Cages at The Jazz Gallery on Wednesday, May 24th, and Thursday, May 25th, 2017. The group features Mr. Tepfer on piano, Or Bareket on bass, and Nate Wood on drums. Sets are at 7:30 and 9:30 P.M. each night. $15 general admission ($10 for members) for each set. Purchase tickets here.