Finding the saxophone's nature: Tivon Pennicott Speaks

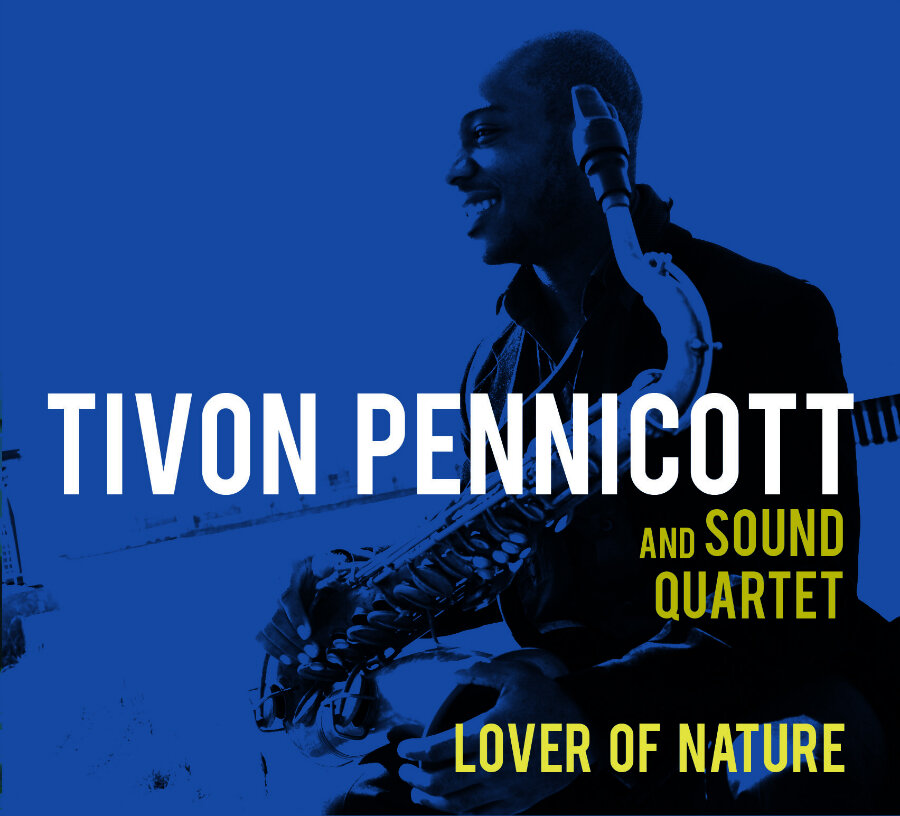

I'm going to let you in on a secret, one that's known to big name jazz performers like Kenny Burrell, Esperanza Spalding, and Gregory Porter, but maybe not the music world at large: Tivon Pennicott is one force of nature on the tenor sax. This young saxophonist isn't without accolades—he was a finalist at the 2013 Thelonious Monk Competition—but throughout his career thus far, Tivon has focused much more on sideman work than stepping out as a leader. Having honed his sound in groups led by the artists mentioned above, Tivon is primed for a musical breakout with the release of his debut record, Lover of Nature (New Phase Records).

This Thursday, February 19th, Tivon will return to The Jazz Gallery stage with a new quartet featuring some immensely talented peers—Keyon Harrold on trumpet, Luques Curtis on bass, and Jamison Ross on drums. We caught up with Tivon this week by phone to talk about his new record and what's next for him.

The Jazz Gallery: Let's start right off with the last track on the album, Lover of Nature. It’s a duet between you and Mike Battaglia on piano. There’s a special connection there, as well as throughout the album. How did you first start playing together?

Tivon Pennicott: Well, Mike and I went to college together, at University of Miami. I’m a year ahead of him, I met him my sophomore year, in 2005. As you know, he’s an amazing pianist, but he has so many other skills, too many to mention right now. He went to school for audio engineering. He wasn’t even in performance, and I had just met him from him wanting to jam. Mike is special. He can pretty much hear anything. He has some of the most incredible ears that I know of anyone. He’s also very theoretical and dissecting of music and theory in ways that I don’t know if I’ve ever heard anybody do. So he’s just a special guy. I’m happy to have known him then, and our friendship has grown through going to school together. When I moved to New York in 2009, he eventually came up as well. I always told him that we were going to start a band together.

So we grew up musically together. That’s where the connection comes from.

TJG: How did Mike’s ear and attention to detail influence your compositional process?

TP: You know, when I was writing all the songs, of course I had a band in mind that I was writing for. But I didn’t do it specifically for Mike. I knew that he would take whatever I wrote and put Mike Battaglia on it. One thing I did make sure of was that anything that I wrote would be able to be played trio, complete as a trio sound, and I knew that in adding Mike... I trusted his musicality to put the right parts in.

TJG: So, back to the beginning of the album—the first track, "Translated," builds around a vamp, with dense clusters of 2nds and 9ths on the piano, but then becomes consistent and metronomic towards the middle, with a slow, strong dynamic buildup. Could you describe your process for shaping your compositions?

TP: Well, when I wrote "Translated," it started out as a series of rhythmically related sections. But I wanted to make sure that the second part wasn’t so obviously related. Like a game, almost. Kind of like a clever way of connecting common rhythms and meter throughout. While I was writing the song I made sure that I had this first section, and then it felt like it needed a contrast. The contrast went straight to something low-key and smooth, and Mike and I traded. It was an opportunity to re-introduce the original riff in a new context.

TJG: How does your compositional approach change from tune to tune? For example, "Observe" is very through-composed, classical, functional, texturally stripped down, where "Come Get Me" is more straight ahead. Does your approach change from tune to tune?

TP: Yeah it does. A lot of these songs were written at different times in my life. As I wrote in the liner notes, each one has a meaning for my experience in New York, either there or leading up to it. So with "Observe," I was basically influenced, or struck, by daily life, my awareness, seeing things around me, seeing the awareness of others. It’s a typical human thing, to observe, but I wanted to express my own experience through the music. So with that energy in mind, I started connecting musical aspects to my experiences. And that’s what came out. It was great, very classical-oriented, and kind of changed step-by- step as I wrote.

About "Come Get Me"—that was actually written a while ago while I was in L.A., but it wasn’t necessarily completed until I moved to New York. That song was always associated with the dynamics of romance, but it was only completed after being in New York and having a coming-of-age experience with the dating of process, with romance and all that. So it’s all connected in that way.

TJG: It seems like you had a relatively formal upbringing, from high school competitions to conservatory training. Who are some of the people who have stood out along your journey?

TP: I think that early on it was important for me to get a grasp on reading, understanding how music works. Just the basics of how music works, understanding harmony in a theoretical way. It really started in my middle school days. I started saxophone at the age of twelve, sixth grade, and I was fortunate to have a band director who was proficient in classical alto. His name was Chad Davenport. He exposed me to new music, as well as challenged me with classical music for saxophone. I enjoyed reading, the game of reading music. He’d say, “Oh yeah, you got that one, well what about this one?” That really helped. To this day, I’ve kept in touch with him, I’ve always been appreciative of him. He’s been a real foundation of mine in terms of musical motivation.

My high school director Stutz Wimmer was equally motivational, and got me into learning the theory of jazz. He sent me to college at University of Miami, made sure I went to a good school. All of this was particularly nice for me, because my background, musically, is very natural. My parents are Jamaican. They’re musically inclined, but don’t know how it works in a theoretical way. I definitely grew up around a very free-spirited household, like “let’s make music” and the importance of groove. Groove was a natural thing in my household. I played drums in church, you know? It was all natural.

Gary Keller in Miami taught me more of the technical aspects of the saxophone. So eventually, I could put it all together, and use my ears, my foundation, and combine it with my technical knowledge that I’d gotten over the years.

TJG: What did you learn from your time with Kenny Burrell?

TP: Well, while I was in college I visited my friend in L.A. I was checking out a class at UCLA. Kenny lives in L.A. So it was like a movie: “Hey man, what’s your name, you sound good!” “Hey, I’m Tivon.” “Hey, nice to meet you,” et cetera. Kenny happened to be performing in the city, and he invited me to play. And he kept calling me after we played. I’ll tell you what, man, that experience... I definitely come from the school of Kenny Burrell. That experience showed me that it was important to value The American Song Book, to really get into the history of jazz, and how things have developed into how they are today. He was a direct source into what was happening. I mean, he was there. I was so fortunate and privileged to be part of his band, learning new music and songs, learning stories of how he grew up in Detroit. There was a lot of growth on my part by being with him.

TJG: Is there anything on Lover of Nature that reflects your experience with Kenny?

TP: Kenny Burrell is in love with Duke Ellington, so every set, he would always feature me on a Duke Ellington song of my choice, usually In A Sentimental Mood. His love for Ellington got me listening to Ellington, and seeing where he comes from. It influenced the variety for me, being adamant about the process of composing and taking it seriously. So I would say that the whole album is coming from an intricate, subtle place. There are a lot of subtleties that I purposefully put there, even if they seem like they’re improvised. I believe in the odyssey of composition. Also, I learned about having a setlist, about how songs can sound good one after the other, and I was thinking about that from being with Kenny Burrell.

TJG: I hear some parallels between your playing and Troy Roberts’ playing. Did you connect at Frost, and who else might have made an early impact on your sound?

TP: Yeah! Troy was actually my teacher for one semester, the first year of college! I was very influenced by his work ethic. He’s a hard worker, and composer. Troy is the man. He’s definitely an influence, in a different way. Troy and I happened to be in the environment of Miami, which kind of lent itself to our kind of sound. I don’t know if it was directly from him. But for some reason, we pay attention to two things. First and foremost is the groove. It has to feel good. Secondly, we both took an interest in advanced rhythmic concepts. I definitely heard that in his music and his compositions. If I hadn’t known Troy, I think I’d still be on the same track. But at the same time, he was a huge inspiration for me, compositionally, and in terms of work ethic.

The main influence I’ve had in writing is just kind of coming from a natural place. I’m kind of just living life, and using what I’ve learned from theory and from my upbringing to create what I’ve been writing. Growing up in a Jamaican household, playing in church, learning how music works in a theoretical way.

I should mention drummer Andrew Atkinson. While I was at Miami we played in a band. He taught me so much about advanced rhythm. He’s a huge influence. We played locally, I would learn his songs, I would write songs. He would focus on metric modulation, and I learned how to be comfortable in advanced rhythmic situations. I recorded on his album Keep Looking Forward. He’s what allowed me to be able to play with drummers like Ari Hoenig. I always liked rhythm, but he pushed it along.

TJG: What’s it like working with Spencer Murphy? His harmonic work on "To Be Counted" is so creative, and I even caught a Rite of Spring quote on "Lifted."

TP: Hah. Spencer’s my man, you know. I moved to New York, and he was doing his Monday night residency at Smalls. I sat in with him, and he was gracious enough to hire me on Mondays. I really like his sound. Spencer is a very knowledgeable person. He listens to a lot of music, and takes pride in knowing a lot of music. Having conversations with him, I learn on a daily basis. I have to have someone like that in my band. He understands groove, pace, a lot of things that I value. He’s also an incredible writer. I’m talking about words and music. That’s who he is, he’s completely himself, and I really appreciate that he is himself. We’re great friends and we play together all the time in various situations.

TJG: How did you get Kenneth Salters involved with the project?

TP: Man, it’s crazy. Maybe a year after I moved to New York, I’d be going to St. Nick’s Pub. That club is closed now, but hopefully it reopens. Anyway, that club is very special to me, because that’s where I met Kenneth, as well as Gregory Porter. It’s a special club. I would sit in on the jam session. Kenneth was there too, he lives pretty close by. He’s really tall, very present person, so he would be sitting in the shadows in the back. He looks scary at first, if you don’t really know him. He’s very quiet, he keeps to himself, he has a lot of thought. But he got up to play one night, and I was just blown away. Wait, who is this guy?! Everything I wanted to hear, he was doing. We started connecting, and would play a lot of duo sessions together. It’s fun to learn from him. He’s very rhythmically advanced, but not only that, his decision-making and touch on the drums are great. Very knowledgeable, organized person. I need that in my life! The whole album is a great, varied group of people that I’ve brought together.

TJG: What can we expect from your February 19th show at The Jazz Gallery?

TP: It’s a different crew, and I’ve been playing with these other guys for a while. I feel like it’s time to explore some different sounds. I have a new group concept, with Keyon Harrold on trumpet, Luques Curtis on bass, and Jamison Ross on drums. I’m very influenced by Mark Turner in a lot of ways. I really like his group with Avishai Cohen, Joe Martin, Marcus Gilmore, you know. It inspired me to do something like that, in terms of instrumentation, but with my sound. I want to write music that deals with my upbringing, but in a very obviously soulful way, something that is even more of who I am as opposed to just looking at the theoretical foundation. I’ve taken some time, and have been writing some carefully-written music. But I want to capture the free-spiritedness of the group too, having no chordal instruments.

TJG: Do you have any plans for another release in the near future?

TP: Yeah, this thing at The Gallery is going to be a debut of a new sound. We’ll continue to develop and play other places, and eventually do a record. That’s the plan. But we want to get used to the music first.

The Tivon Pennicott Quartet plays The Jazz Gallery on Thursday, February 19th, 2015. The group features Pennicott on saxophone, Keyon Harrold on trumpet, Luques Curtis on bass, and Jamison Ross on drums. Sets are at 8 and 10 p.m. $15 general admission ($10 for members) for the first set, $10 general admission ($8 for members) for the second. Purchase tickets here.