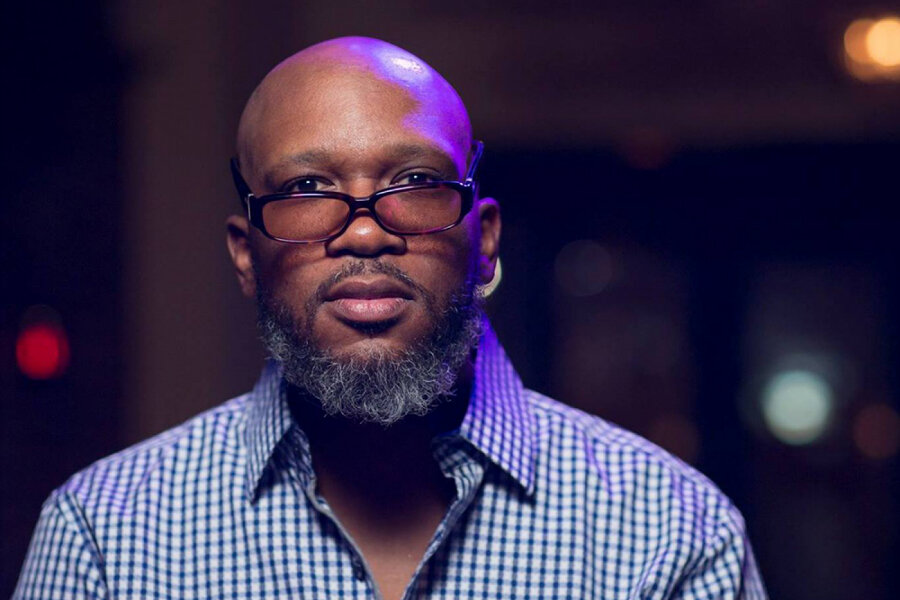

Knowledge and Evolution: Orrin Evans Speaks

Pianist Orrin Evans is seemingly always on the move. If he's not putting out a new record of his own (he's released twenty-five as a leader or co-leader in his career), he's producing someone else's. Or leading a weekly jam session at WXPN's World Cafe in Philadelphia, or programming Wednesday night concerts at the club South, just across town.

Evans has had a long relationship with the Gallery, but has yet to play in our new space on Broadway. This Friday, July 15th, we welcome Evans's quartet, along with special guest vocalist Joanna Pascale, to our stage for two sets. We caught up with Evans this week to talk about his relationship with Ms. Pascale, and his thoughts about his home city of Philadelphia.

The Jazz Gallery: In Joanna’s bio, she writes of how you gave her a debut at your jam session back in the day. Since then, how have you watched her grow as a singer, and how have you grown together as musicians?

Orrin Evans: The period right after that, she went to Temple University while I was still in New York, and we remained connected. A few years later, after she graduated from Temple, she ended up having a full-time residency at the Loews Philadelphia Hotel, where she played several times a week for ten years. I got a chance to play with her and watch her grow as a singer and entertainer and bandleader. She employed different people every week for ten years. I watched her learn how to play for different audiences. That room wasn’t a ‘jazz’ audience per se; it was just a hotel. But it gave her a chance to find herself, and prepared her for all the projects that came after that. It’s been a pleasure watching her grow. We’ve played in New York twice together before, but I haven’t played at The Gallery as a leader since it moved, so it’s really exciting to get back there and start playing again, and to bring some musical family from back in the day.

TJG: You recently produced her latest album, Wildflower, right? What was it like working with her on her music in that setting?

OE: It was amazing. It was a labor of love, everybody was there to help and to be a part of the process. That energy is really encouraging and inspiring. Watching her jump into the arena with all of these people was amazing as well. She had never played with Christian McBride, she hadn’t played with Obed [Calvaire], she hadn’t played with Vicente [Archer]. She and Bilal went to high school together, but hadn’t done anything since then. So it was really good watching her do what she does in this foreign territory, for lack of better words. Not that she wasn’t used to the studio, or to playing with different people, but going into a studio with people you haven’t really played with before is a brave thing to do, and she did it great.

TJG: So in the studio, what kind of work were you doing with her?

OE: I played on a portion of it, but aside from that, I look at the producer role as just being there for all aspects of the recording. Paying people and dealing with the busywork so everyone can just sing or play, assisting with arrangements, making sure there were copies: My role was to help Joanna get what she needed, and to help her see her vision and get this record to be exactly what she wanted it to sound like. I would make suggestions on instrumentation and arrangements, and so it’s kind of a full plate. In other roles, you might just be the person in the booth listening to playbacks, but I’m more of a hands-on person, and she really allowed me to get in there and become a part of it.

TJG: So how did you decide to feature her with your quartet at The Jazz Gallery?

OE: We’re actually doing some other work, heading towards Massachusetts and farther north. While we were booking, I said “You know what, I haven’t played at The Gallery in a long time, why don’t we try to pass through there on the way north?” It worked our perfectly. We booked the gig back in October, so talking with you now is kind of putting the pressure on me—I can’t believe the gig is already next week. We’re playing at the Buzzards Bay Musicfest after that, a jazz festival up in New England.

TJG: So you’re back in Philly now. But you’re constantly on the road, and you’ve spent some time living in other places, including New York. Tell me a little about your relationship with Philadelphia today.

OE: Philadelphia is a place that I will always love and respect, because I’ve learned so much from the people I’ve met here throughout the years. I do get frustrated by how people look at the arts here. But my mortgage is affordable, I can park my car, I have a little back yard, my wife has a garden, and I can get to the New Jersey Turnpike in twenty minutes. For those reasons, I live in Philadelphia, but I’ve always had a love-hate relationship with this place. I moved back here almost twenty years ago, when my kids were younger. We moved here so they could go to school here. But now they’re both out of school. Will I move back to New York? I’m not sure. I still love the peacefulness of being able to park my car, and I can get to New York in no time. As far as my relationship to the musical scene here, it’s one that I want to see get better. Will it get better? I don’t know, but I won’t stop trying.

TJG: So what frustrates you, and how are you trying to change things?

OE: I’ve always made myself accessible to run different series. I’m doing a series right now at a club called South, which has partnered with The Jazz Gallery. I’m presenting different artists every Wednesday. Last night was Robin Eubanks, the week before was Nicholas Payton, we had Jeff Tain Watts. I’ve been bringing people since October. But that series probably won’t last through August, because I haven’t really been getting the support of the audience. You know, these are half-price events, for artists who come from far away like Jason Moran, Buster Williams, Wallace Roney. They come to show their support for the city and for what I’m trying to do, but I can’t get the numbers. I can’t get people to come out on a Wednesday night. So that answers both questions, what frustrates me and what I’m trying to do about it. I didn’t just move to New York and say “Forget about Philadelphia.” I’m still trying to be a part of the scene. But Philly is a place that looks right back at you and says “Yeah, we don’t want it.” They like their cheesesteaks like this, their hoagies like that, and they’re not gonna support the stuff that they don’t want. That’s cool, you know, because somebody wants what I’m serving. I don’t hate Philly, but I understand the limitations that this beautiful city has.

TJG: Why do you think you can’t get the numbers? Do you think people aren’t going out to hear live music anymore?

OE: I don’t think it has anything to do with music. There’s a great book by W.E.B. Du Bois called The Philadelphia Negro that might speak more specifically to what I’m talking about. Philadelphia is no more different that Brooklyn. When I lived in Brooklyn, there were people on my block that hadn’t gone over the bridge to Manhattan in years. They’d say things like “One day, man, I’m gonna go over there and check out one of your shows.” They’re in their own little world. The only difference is that they’re in Brooklyn. That’s a great place to be in your own little world, you know what I mean? [laughs]. Or in Manhattan, where you don’t go to Queens or Brooklyn, but at least you’re in New York. When you’re in your own little world in Philly, that’s all you got is Philly. We’re basically the town that that says “This is how we do it, so you better bring it just how we like it.” We do the same thing to our sports teams. If someone thinks they’re gonna come in and play the game a different way, they’re going to be compared to everyone that’s played before them. It happens across the world, but when it happens in a small town—and yes, I’m calling Philly a small town because we have a small town mentality—it’s not good for you. Some of my best friends have never come down town to see me play, because they don’t go down town. “Where am I gonna park? Where am I gonna put my car? What will I do?” That’s the problem with Philly.

TJG: Do you think it’ll ever change?

OE: I have to learn to not care. And I know that sounds rough, but it takes up too much time. I can only do what I know is right. I’ll always offer up information, I’ll always provide good entertainment, I’ll always bring my friends and family to town. If you don’t show up you don’t show up, but I’ll continue to do what’s right.

TJG: In a promo video for your trio album The Evolution of Oneself, you discussed how “Evolution is driven by need and desire for change.” Why is change important for self-expression in jazz?

OE: There’s only twelve notes in the chromatic scale. You would think that about twenty years you’d know what the possibilities of those twelve notes are. You’d probably think you know all the ways you could play those notes in a B-flat blues. Once you accept that that’s all there is to do with those twelve notes, that’s all you're going to play, that’s all you’ll be able to sound like. But if you step back and ask yourself how to play differently, how to rearrange the notes and tweak your approach, those same twelve notes can be opened up to so many new possibilities.

It’s no different than food. I love food, I’m kind of a foodie. You can say to yourself, “There’s nothing wrong with this burger, I’ve been eating this burger all my life.” But how about if you stuff it with something unexpected? My favorite way to look at life is as if it’s the TV show Chopped. It’s on the food channel, and I love it. I think we should all look at life that way: You open a basket, and no matter what’s in it, you have to make a great meal out of it. The best things I see on the show are like when a big piece of steak comes out of the basket of a vegan chef. You’re a chef, and you have to do something with it. You may be a vegan, but you’re a chef. What can you do with it? There are still possibilities outside of what you may know. You open the basket and it’s got jelly and shrimp. What the hell are you gonna do with jelly and shrimp? [laughs]. There are endless possibilities. That’s how you evolve as a person, a chef, a musician. You may have roots, but you recognize and explore the possibilities.

TJG: So when do you find yourself in that mindset? Is it when you’re improvising, when you’re arranging? When do you feel that innovation most acutely?

OE: I try to feel it every time I sit down at the piano or computer to compose and play. To be honest, I feel it when I get in my car, even when I wake up in the morning. I turn my GPS on even when I know where I’m going, because I like to see if maybe they’ve got a different route for me that I wouldn’t have considered. “Take a right here—Whoa, I never would have taken a right here!” [laughs]. I take those risks and try to evolve every day. I’m doing something different this week that I haven’t done in a long time.

TJG: And what’s that?

OE: Not drinking! [laughs]. It’s going great. I’m sitting at a bar right now, drinking a ginger ale and eating lunch. I didn’t stop for any particular reason; I’ve never stumbled out of a bar drunk. But I just wanted to try something new. It may last one more day. When I’m on the plane, hopefully I’m upgraded to first class and they’ve got free vodka [laughs]. But however long it lasts, I’ve tried something new.

TJG: So you’ve got two boys, right? How have they changed your perception about what’s important in music?

OE: I had them early, so my perspective on music, life, and fatherhood all evolved at the same time. I don’t think my kids ever ‘changed’ my perspective on music. My oldest was born when I was eighteen. My youngest was born when I was twenty-three. I was a kid. I had to grow as a husband, father, and musician all at once. Everything has had an impact, but I don’t think there was a point where I changed the way I saw music, because my kids have always been a part of my musical journey.

TJG: I was at your recent concert at Princeton University, where you sang a song towards the end of your set. Do you sing often?

OE: That’s whenever I feel the spirit. Lately I’ve been feeling it more. I just feel the room out and see if it’s time. Sometimes it’s not, and I find that out after I start singing [laughs]. But it’s something I enjoy doing.

TJG: Think you might sing with Joanna at The Gallery?

OE: Never. I would never do that [laughs]. If it’s my gig and there’s a singer on it, very rarely would I do it. It depends on how ballsy I feel, or if I’m playing with the small group or the big band.

TJG: Aside from trio and quartet work, what’s the news with the Captain Black Big Band? And what’s the next release or project going to be?

OE: We’re starting to work on another record, getting things together step by step. It’s a combination of my music and other band members’ music. It’s a labor of love. I love doing it. My next record is coming out in October, it’s called Knowing Is Half The Battle. It features Kevin Eubanks and Kurt Rosenwinkel, and the trio of Luques Curtis and Mark Whitfield Jr, as well as Caleb Wheeler Curtis on sax. New music, released on October 15th, and I’m really looking forward to it.

TJG: Orrin, thanks for taking the time to speak with me. We can’t wait for the show.

OE: Thanks a lot man, I appreciate it, great talking with you.

The Orrin Evans Quartet with special guest Joanna Pascale plays The Jazz Gallery on Friday, July 15th, 2016. The group features Mr. Evans on piano, Joanna Pascale on vocals, Stacy Dillard on saxophone, Luques Curtis on bass, and Mark Whitfield, Jr. on drums. Sets are at 7:30 and 9:30 P.M. $22 general admission ($12 for members) for each set. FREE for SummerPass holders. Purchase tickets here.